Measuring the Motives for Charitable Giving

Charitable giving plays an important role in the U.S. economy. In 2016, individuals gave $282 billion to churches, museums, universities, and myriad other institutions.1 A variety of issues pertaining to donative behavior have been covered in the economics literature. Two of the more important ones have arisen in discussions of the motivations for giving. The first is reciprocity: do people donate because they expect something in return? The second is affinity: what factors influence whether an individual develops a feeling of a community of interest with a charitable institution?

In a series of papers, we have examined these issues through the lens of alumni donations to universities. The determinants of alumni donations are of independent interest because of their importance in university budgets — donations were about $41 billion in 2016 and covered roughly 10 percent of institutions' expenses.2 Endowments, another source of revenue, are composed in part of previous donations. Cuts in state aid to public universities in recent years and changes in tax incentives for donations embodied in the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act have brought questions about voluntary support of higher education to the fore. Further, universities have a unique structure and relationship with their alumni, a relationship that begins when individuals are students and which may extend decades beyond that time. Importantly, the relationships among alumni, solicitors, and the university itself are generally more clearly defined than for most charities. This makes higher education particularly useful for studying how an institution attempts to engender feelings of affinity among potential donors.

Most of the research described here is based on extensive proprietary information we received from a private, selective research university, which we call Anon U. These data included information on alumni such as age, ethnicity, gender, SAT scores, field of study, post-graduate degrees, and family members who also attended Anon U, as well as information on every gift they made to the university after graduation. In addition, the development staff at Anon U provided us with detailed explanations of their solicitation practices.

Reciprocity

Economists have long recognized that people are not entirely selfish; altruism is an important part of human behavior. That said, some charitable behavior is doubtless driven in part by self-interest. In particular, donors might expect something in return for their gift, such as prestige, tangible benefits like gifts or access to social events, and the ability to signal their virtue to others.

The Anon U data allowed us to make a rough estimate of the extent to which donations were due to a particular kind of reciprocity, namely, the hope that donations will help their children gain acceptance to the university. Although Anon U makes no promise whatsoever that donations will increase the likelihood of acceptance, this view that they could is widespread.

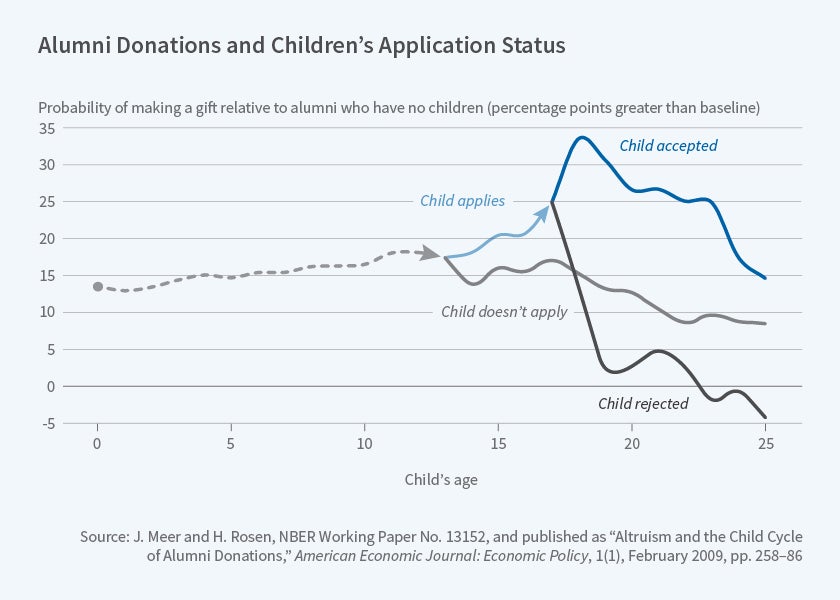

To assess the impact of this belief on donative behavior, we examined the relationship between an alumnus' or alumna's giving and the age and application status of his or her children.3 If alumni believe that donations increase the probability of their children getting admitted, then giving will increase as their children near application age, and vary systematically with whether they apply and are accepted. We call this pattern "the child-cycle of alumni giving."

Figure 1 illustrates the child-cycle pattern generated by our Anon U data. The amount donated to the university is plotted as a function of the alumnus' or alumna's eldest child's age, relative to alumni who have no children. Those with a child donate more even when the child is very young, possibly because alumni with children have more interest in education in general. At age 14, we divide the sample between those whose children eventually apply to Anon U and those who do not. Giving increases sharply for the parents of future applicants, while it remains unchanged for the parents of non-applicants. At age 18, we divide the sample of applicants into those who were accepted and those who were rejected. Giving by parents of rejected applicants drops dramatically — back to the level of childless alumni. All of this is consistent with the notion that an expectation of reciprocity is driving at least some donations. This finding is supported by Kristin Butcher, Caitlin Kearns, and Patrick McEwan's study of data on giving at a women's college.4 They also find that giving follows the child-cycle pattern and that alumnae with female children, who hence were feasible candidates for admission, gave more than those whose children were male, other things being the same.

To investigate further the notion that reciprocity influences donation decisions, we examined the proportion of alumni parents' giving that was directed toward specific purposes, such as athletic teams. We found a strong increase in such directed giving when their children were attending the university and a strong decrease after graduation, suggesting that parents were financing their child's own activities, and providing more evidence of self-interested motivations for giving. Related research using field experiments also shows that donors to universities are responsive to opportunities to direct their giving to specific causes.5

Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that about half of giving by alumni whose children apply to Anon U is due to self-interest driven by hopes for reciprocity for their children. This is a lower bound for the overall role of self-interest, though, because our data do not allow us to discern other, non-child-related motivations.

A rather different type of reciprocity arises in the context of financial aid. Recipients of financial aid may feel gratitude toward their alma mater and therefore "give back" later in life. But they may also feel resentment, particularly if the aid comes in the form of student loans. The obligation to repay such loans, of course, can also reduce the capacity of alumni to donate.

We analyzed the relationship between giving and financial aid and found that the presence of a student loan per se decreases the probability of making a gift.6 In addition, the amount donated falls with the size of the loan. We show that these effects are unlikely to be driven by lower income, but rather may reflect annoyance with loans that reduces affinity for the school. Scholarships, on the other hand, have no impact on the likelihood of giving. With respect to the amount given, we find that scholarship recipients give less conditionally on making a donation than their non-scholarship counterparts. At the same time, though, the amount donated does increase with the size of the scholarship, suggesting that reciprocity plays a role.

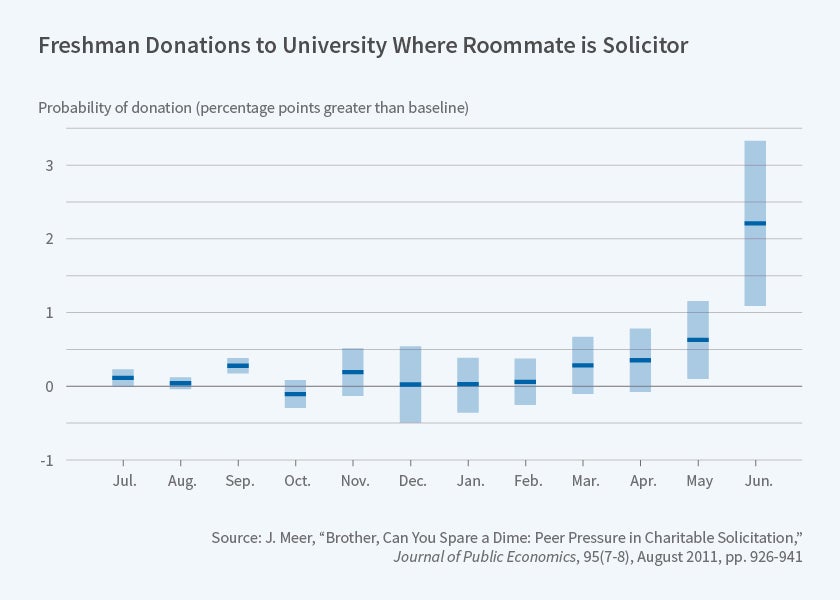

Reciprocal behavior can be driven by social pressure as well.7 This hypothesis is challenging to investigate, though, because social relationships are rarely random. A correlation in giving within a social network might be driven by common interests that lead to self-selection into that group. Thus, for example, observing that a person fundraises for a charity and his or her friends donate to that charity does not necessarily mean that their giving was driven by a desire to avoid social pressure. At Anon U, however, freshman-year roommates are assigned in a manner that is random with respect to any characteristics that could plausibly affect later-life giving.

Common experiences as roommates could create a spurious correlation between volunteering as a solicitor for the university by one roommate and giving by another. In that case, though, there would be a correlation between volunteering in any capacity for the university, including activities with no solicitation component, and giving by roommates. The processes that Anon U employs for organizing its volunteering and solicitation activities turn out to provide a useful framework for addressing this concern. Solicitations are generally impersonal, through letters and emails, until June, the last month of the fiscal year. At that point, alumni volunteers call classmates to raise funds for the university. High affinity for the school due to common experiences would lead to higher giving throughout the year; elevated giving only in June strongly suggests a response to social pressure.

As illustrated in Figure 2, this is precisely the pattern that emerges. Having a former freshman-year roommate who volunteers in a non-solicitation capacity for the university has no impact on giving, while having a solicitor roommate increases giving by about 10 percent. Importantly, this effect is limited to donations made during the time when personal solicitations are conducted. Furthermore, giving is elevated in the years in which one's former freshman-year roommate is a solicitor, compared to those in which he or she is not. In follow-on work, we also find that direct, personal solicitations can have an impact even after multiple impersonal solicitations, further demonstrating the impact of social pressure.8

Finally, a field experiment at Texas A&M University conducted by one of us (Meer) with Catherine Eckel and David Herberich examines whether gifts to prospective donors from a charity — so-called donor premiums — increase donations by creating a desire or a sense of obligation to respond to a subsequent solicitation.9 On the other hand, distaste for the costs associated with this solicitations strategy could reduce giving.10

We randomly assigned a group of alumni to a number of treatments. Some were sent unconditional gifts included in the solicitation — Texas A&M luggage tags — while others were offered a gift conditional on their donation, with some having the option to opt out of the luggage tag. A control group was solicited with no gift offer. Responses were higher for those who were sent a gift on the front end than for those who were not, but not nearly enough to make up the cost. The promise of a gift had no impact on the size of donations. Few took the opportunity to decline the conditional offer when making a gift, suggesting that donors do place value on these gifts.

Our discussion so far has mentioned at several points the importance of affinity for a charity as a motivation for giving. We next turn to how universities form that affinity.

Creating Affinity for the Long Term

Universities can form stronger bonds with individuals earlier in life than most charities, a built-in advantage that enables long-term relationships. In several papers we have investigated the factors that engender affinities between a university and its alumni. At Anon U, participation in the majority social culture as an undergraduate, such as playing a varsity sport or belonging to social organizations such as sororities and fraternities, is strongly correlated with future giving.

The large role played by athletics at U.S. universities, often justified on the grounds that it leads to greater alumni engagement, led us to investigate this question in greater depth.11 While previous work has focused on whether big-time sports like football and basketball impact giving,12 we looked at the success of the team to which the alumnus or alumna actually belonged. For men, having won a conference championship as an undergraduate tended to increase future giving, primarily to the athletic fund, as opposed to the general fund, while there was little effect for women. After graduation, when an alumnus' former team won a conference championship, on average he increased giving to both the general and athletic funds, while for alumnae, there was no impact.

Football and basketball conference championships did little to increase giving, though we note that Anon U does not generally have a high profile in those sports. At schools with more visible football and basketball programs, the effects of success for those teams might be larger and more robust. Nevertheless, there is no reason to believe that former athletes at such institutions fail to develop an affinity for their own teams — our results on the importance of own-team championships could very well generalize. To the extent that this is true and universities care about turning their undergraduates into future donors, it would seem that universities should nurture broad varsity athletic programs.

Dovetailing with our work on the child-cycle of giving, we also examined whether families form bonds with universities that lead to greater overall donations, a frequent justification for legacy preferences in admissions.13 We find that alumni whose children, nieces, or nephews attended Anon U donate substantially more than alumni who do not have a member of the younger generation attend. On the other hand, while alumni whose parents, aunts, or uncles attended Anon U donate more than their classmates whose relatives did not, the effect is smaller. And having a grandparent who attended Anon U does little to change giving.

Affinity for the university may induce donations for a few years after graduation, when memories are fresh. But universities want alumni to continue to donate even long after they have completed their studies, especially as they reach their peak earning years. This leads to the important question of whether giving when young has an independent effect on giving later in life: is charitable giving habit-forming? University fundraisers at many institutions certainly seem to believe that it is. They devote considerable resources to inducing young alumni to give even token sums, in the hope that they will continue to do so, and in greater amounts, later in life. In the Anon U data, there is a strong correlation between the probabilities of giving when young and later in life. But such a correlation by itself is not enough to demonstrate that habit formation is important in this context.

In order to identify the presence of a habit-formation effect, we require some variable that exerts a transitory effect on giving that is uncorrelated with the alumnus' or alumna's own general tendency to donate. The two considerations discussed above — having a former freshman-year roommate who is a solicitor, and athletic performance of an alumnus' former varsity sports team — fit the bill. Examining the giving patterns induced by these external inducements to donate allows us to isolate the impact of donative behavior when young on giving when older.14 Estimates that fail to account for unobserved affinity suggest that the amount of giving when young drives giving when older. However, after correcting for spurious correlation, we find that the frequency of donating when young is the more important determinant of the size of gifts made in later years.

Another dataset, the survey of Giving and Volunteering in the United States, permits further exploration of habit formation. These data allow us to estimate the relationship between engaging in fundraising and volunteering at age 18 or younger and giving and volunteering as an adult.15 Controlling for the volunteerism of parents helps reduce spurious correlation driven by family factors that could induce an individual to exhibit altruistic behavior when young and when older. Both fundraising and volunteering when young have a substantial positive impact on the likelihood of donating and the amount given as an adult. This relationship holds across all types of charities, including education-related ones. Once again, this provides suggestive evidence of habit formation in charitable giving.

Even in the presence of the interaction between the affinities developed early in life and habit formation, giving tends to drop off as alumni enter old age. Indeed, virtually all statistical analyses of charitable behavior suggest a negative relationship between old age and giving.16 We examine late-life giving to Anon U to investigate the mechanisms behind this empirical regularity. To do so, we supplement our data with information extracted from obituaries published in the alumni magazine. Since we know when an alumnus or alumna passed away and, in many cases, the cause of death, we can separately determine the impact of age and of the approach of death. We replicate the negative relationship between age and donations found in the literature, but show that it is driven primarily by approaching mortality. We argue that our results are unlikely to reflect reduced resources at the end of life, but rather the diminished capacity or distractions of a final illness. Given the aging of the Baby Boom generation, inter vivos end-of-life donations and bequests will likely play a substantial role in the financing of charities over the next two decades.

Endnotes

Giving USA, "Total Charitable Donations Rise to New High of $390.05 Billion," June 12, 2017, https://bit.ly/2spZqlL

Council for Aid to Education, "Colleges and Universities Raise $41 Billion in 2016," February 7, 2017,

J. Meer and H. Rosen, "Altruism and the Child-Cycle of Alumni Giving," NBER Working Paper 13152, June 2007, and published as "Altruism and the Child Cycle of Alumni Donations," American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1(1), 2009, pp. 258–86.

K. Butcher, C. Kearns, and P. McEwan, "Giving Till it Helps? Alumnae Giving and Children’s College Options," Research in Higher Education, 54(5), 2013, pp. 481–98.

C. Eckel, D. Herberich, and J. Meer, "A Field Experiment on Directed Giving at a Public University," NBER Working Paper 20180, May 2014, and Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 66, 2017, pp. 66–71.

J. Meer and H. Rosen, "Does Generosity Beget Generosity? Alumni Giving and Undergraduate Financial Aid," NBER Working Paper 17861, February 2012, and Economics of Education Review, 31(6), 2012, pp. 890–907.

J. Meer, "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime: Peer Pressure in Charitable Solicitation," Journal of Public Economics, 95(7-8), 2011, pp. 926–41.

J. Meer and H. Rosen, "The ABCs of Charitable Solicitation," NBER Working Paper 15037, June 2009, and Journal of Public Economics, 95(5-6), 2011, pp. 363–71.

C. Eckel, D. Herberich, and J. Meer, "It's Not the Thought That Counts: A Field Experiment on Gift Exchange and Giving at a Public University," NBER Working Paper 22867, November 2016, and forthcoming in The Economics of Philanthropy.

J. Meer, "Effects of the Price of Charitable Giving: Evidence from an Online Crowdfunding Platform," NBER Working Paper 19082, May 2013, and Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 103, 2014, pp. 113–24.

J. Meer and H. Rosen, "The Impact of Athletic Performance on Alumni Giving: An Analysis of Micro Data," NBER Working Paper 13937, April 2008, and Economics of Education Review, 28(3), 2009, pp. 287–94.

J. Martinez, J. Stinson, M. Kang, and C. Jubenville, "Intercollegiate Athletics and Institutional Fundraising: A Meta-Analysis," Sports Marketing Quarterly, 19(1), 2010, pp. 36–47.

J. Meer and H. Rosen, "Family Bonding With Universities," NBER Working Paper 15493, November 2009, and Research in Higher Education, 51(7), 2010, pp. 641–58.

H. Rosen and S. Sims, "Altruistic Behavior and Habit Formation," Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 21(3), 2011, pp. 235–53.

J. Meer and H. Rosen, "Donative Behavior at the End of Life," NBER Working Paper 19145, June 2013, and Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 92, 2013, pp. 192–201.