Means Testing Social Security: Income Versus Wealth

A host of factors, from the choice of income- or wealth-testing to how to treat single versus married households, makes the effect of "means testing" sensitive to details of implementation.

In 2015, the annual cost of Social Security retirement benefits equaled 14.1 percent of workers' taxable income. By 2038, it is projected that the cost will amount to 16.6 percent. Future Social Security tax revenues are projected to fall short of future benefit commitments.

The prospect of large, unpopular, tax increases or large, unpopular, benefit cuts has focused attention on using "means testing" to reduce Social Security payments for beneficiaries who are relatively well-off. Means testing can, however, be implemented in various ways, and as Alan Gustman, Thomas Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai demonstrate in Distributional Effects of Means Testing Social Security: Income Versus Wealth (NBER Working Paper 22424), different approaches affect benefits for different households in different ways. The distributional consequences of means testing are sensitive to the way the means test is designed.

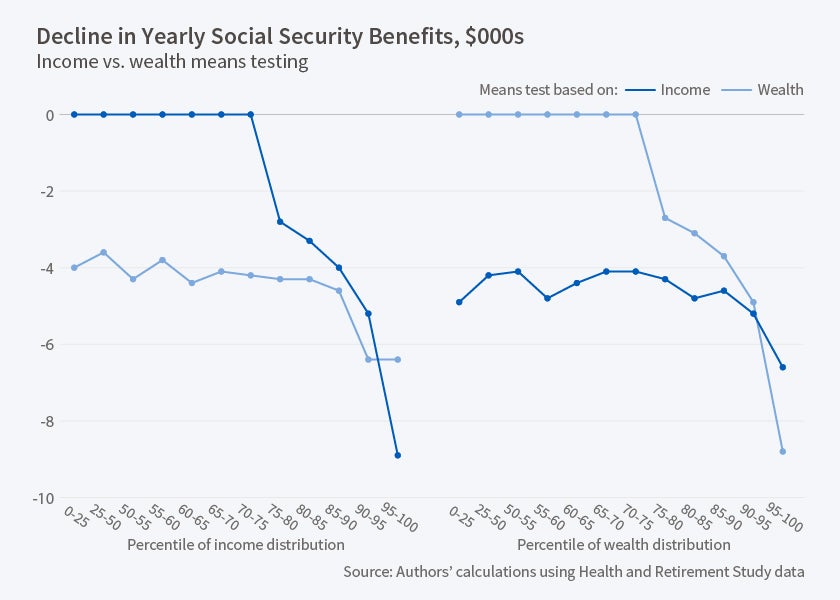

Means tests reduce payments for those with wealth or income above certain levels. To show how different means tests affect different people, the researchers construct a test designed to reduce the average Social Security benefits of those in the upper quarter of the wealth distribution by $5,000 a year. They also construct a test that reduces the benefits of those in the upper quarter of the income distribution by the same average amount.

The authors use the Health and Retirement Study sample of individuals aged 69 to 79 to assess the effects of the different tests. Of the sample, 35.4 percent was in either the top quarter of the income distribution or the top quarter of the wealth distribution, but only 14.5 percent of the sample was in the top quarter of both distributions. Thus if the means test was applied to those in the top wealth quartile, someone who believed that income in the top quartile was a better basis for means testing would find that only 41 percent of those whose benefits were reduced were part of their target group (14.5/35.4 = 0.41).

The average Social Security benefit for an individual in the top quarter of the income distribution was $16,400 in 2010. An income-based means test that reduced the average Social Security benefit for this group by $4,900 would reduce benefits by about 30 percent on average. The average reduction for those in the top quartile of the wealth distribution would be similar if the means test applied to wealth. Among the 14.5 percent of the individuals who are in both the top income and the top wealth quartiles, the average benefit reduction would be $8,600 if the test was applied to wealth.

The distributional consequences of means tests change if the unit of measurement changes from an individual to a household. They change if married households and single households are considered separately. They change if housing wealth is included. They depend upon whether a means test's measures of income and wealth are calculated before or after taxes. Means testing at program entry would reduce benefits more for younger retirees than older ones simply because younger people have not lived on their retirement resources for as many years.

—Linda Gorman