To Change, or Not to Change? Just Flip a Coin

Study participants who made a change reported months later that they were "substantially happier" than those who did not.

When faced with deciding whether to make a change, people may be too cautious for their own good. So Steven D. Levitt concludes on the basis of a study using social media and the toss of a virtual coin. Levitt presents his findings in Heads or Tails: The Impact of a Coin Toss on Major Life Decisions and Subsequent Happiness (NBER Working Paper 22487).

With a posting on his website, Levitt invited individuals who couldn't make up their minds about matters both major (like divorce) and minor (such as changing hair color) to avail themselves of a randomized coin toss. "Heads" would signify a recommendation for change.

"While it might seem implausible that anyone would come to such a website and flip a coin, much less follow the dictate of the coin toss, the results obtained speak to the contrary," Levitt reports, noting that more than 20,000 "coins" were flipped by participants during the year-long study.

Individuals whose virtual coin turned up heads were 25 percent more likely to make a change than those whose coin flip yielded tails. And, based on what they reported in two follow-up surveys over a six-month period, the nudge of a coin toss was just what these participants needed. Regardless of their responses to the coin tosses, participants who decided to make a change reported that they were substantially happier than those who did not.

Coin tossers were re-surveyed two months and sixth months after the initial coin toss. Additionally, before the coin toss, they were encouraged to identify a friend or family member to verify the outcomes. The third parties were also surveyed two months and six months after the coin toss.

Levitt points out that the coin-toss experiment provided a way to isolate change itself as the reason for greater happiness. "Before the coin toss, those who will get heads are, in expectation, identical in all respects to those who will get tails," he writes. Before making the coin toss, participants were asked to forecast the probability they would make a change. Comparing their predictions with their subsequent behavior offered further evidence of the impact of the coin toss.

Across the spectrum of predictions, those whose coin flip came up heads were more likely to have made a change than those whose coin turned up tails. The gap was narrowest among those who were most doubtful that they would make a change.

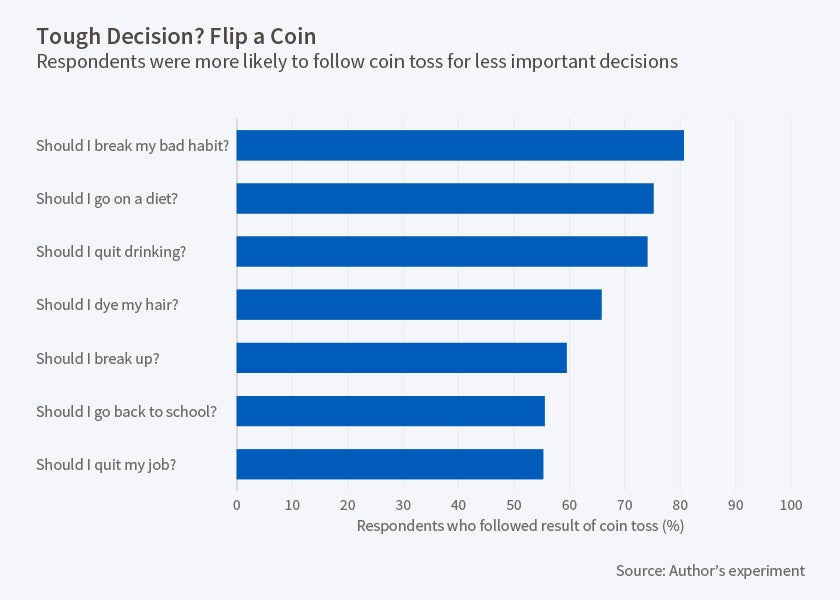

The coin toss was more influential in cases involving less important decisions. The highest compliance rate—more than 80 percent—was on the question, "Should I break my bad habit?" Only one question—"Should I move?"—seemed unaffected by the outcome of the coin toss.

Overall, Levitt writes, the coin study suggests "the presence of a substantial bias against making changes when it comes to important life decisions, as evidenced by the fact that those who do make a change report being no worse off after two months and much better off six months later."

—Steve Maas