Are Publicly Insured Children Less Likely to Be Hospitalized?

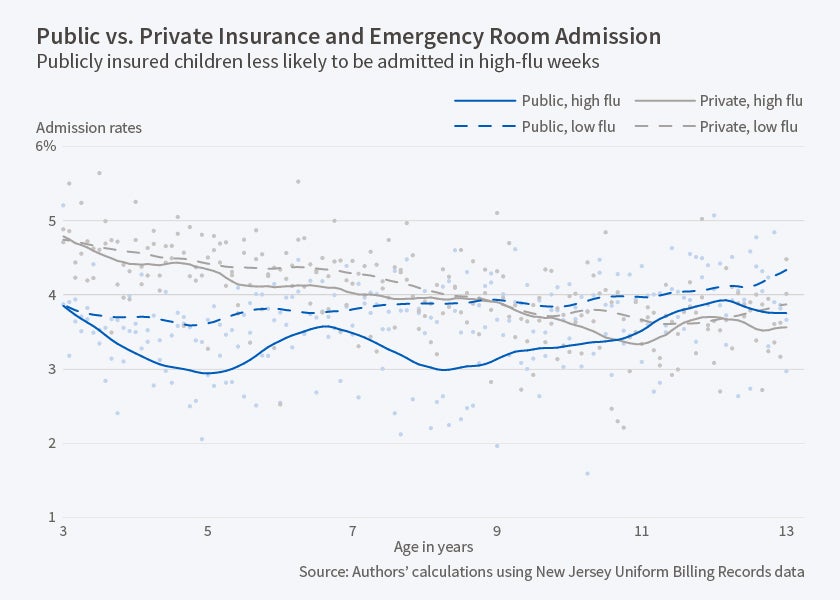

Yes, but this may reflect excessive admission of those who are privately insured rather than under-admission of those who are publicly insured.

Children covered by private health insurance are more likely to be admitted to the hospital after a visit to the emergency room than children covered by a public health plan, such as Medicaid or the State Children's Health Insurance Program. This is the conclusion of Diane Alexander and Janet Currie's study, Are Publicly Insured Children Less Likely to Be Admitted to Hospital Than the Privately Insured (and Does It Matter)? (NBER Working Paper 22542). The study is based on an analysis of the health records of all children between the ages of three months and 13 years treated at a New Jersey hospital emergency room between 2006 and 2012.

Hospitals typically are paid more per patient-day by private health insurance plans than by Medicaid or state health plans. This creates an incentive for hospitals to allocate beds first to the privately insured, and then, after meeting private insurance demand, to those with public insurance.

The researchers recognize that there may be differences between privately and publicly insured patients other than type of insurance that could explain the differential hospitalization rates. Therefore, they rely on exogenous variation in the demand for hospital beds generated by local swings in the intensity of influenza outbreaks to separately identify the effects of hospital and patient behavior. When hospitals are overwhelmed with adult flu patients, the gap in admission rates between publicly and privately insured patients grows for both flu patients and all other diagnoses. These differences persist even after controlling for detailed diagnostic categories, and when comparing publicly and privately insured patients at the same hospital.

Despite the differences in hospitalization rates, the researchers find no discernable differences in health outcomes, such as future hospitalizations or the likelihood of a repeat visit to the emergency room. They therefore conclude that "our results raise the possibility that instead of too few publicly insured children being admitted during high flu weeks, there are too many publicly and privately insured children being admitted most of the time."

—Matt Nesvisky