When Temporary Tax Incentives Work, and for Which Firms

Allowing accelerated depreciation of capital equipment raised investment an average of 10.4 percent a year between 2001 and 2004 and 16.9 percent between 2008 and 2010.

Temporary tax incentives boost capital equipment purchases when companies see an immediate benefit, according to research by Eric Zwick and James Mahon in Tax Policy and Heterogeneous Investment Behavior (NBER Working Paper 21876). This is especially the case for small firms, which respond much more strongly than large firms to those tax breaks.

"Bonus depreciation has a substantial effect on investment," the researchers find. Accelerated depreciation on capital equipment raised investment an average of 10.4 percent a year between 2001 and 2004 and 16.9 percent a year between 2008 and 2010, according to their estimates.

These estimates are substantially higher than estimates from most previous studies. One reason for the disparity is the authors' focus on much smaller enterprises than have been examined in previous research. Examining more than 120,000 firms from 1993 to 2010 using Internal Revenue Service data from unaudited corporate tax returns, the researchers compare investment by companies in industries that buy mostly short-duration capital against those that buy mostly long-duration capital. Only the latter group receives substantial benefits from bonus depreciation and thus responds strongly to this tax incentive.

While large firms account for most investment spending — the top 5 percent of firms are responsible for more than 60 percent of total investment — the researchers find that the responses of small and medium-size firms matter for aggregate estimates of the policy response. The authors estimate that, when adjusting for the response of small firms, the elasticity of investment spending with respect to the after-tax price of investment goods is 27 percent greater than the elasticity for the largest firms.

If a firm is currently reporting a loss, and it is in a "tax-loss" position, it will not receive the benefits from accelerated depreciation until a future date when it returns to profitability and begins to pay taxes. The researchers use this feature to study the importance of immediate tax benefits versus future ones. "Firms only respond to investment incentives when the policy immediately generates cash flows," they conclude. "This finding holds even though firms can carry forward unused deductions to offset future taxes."

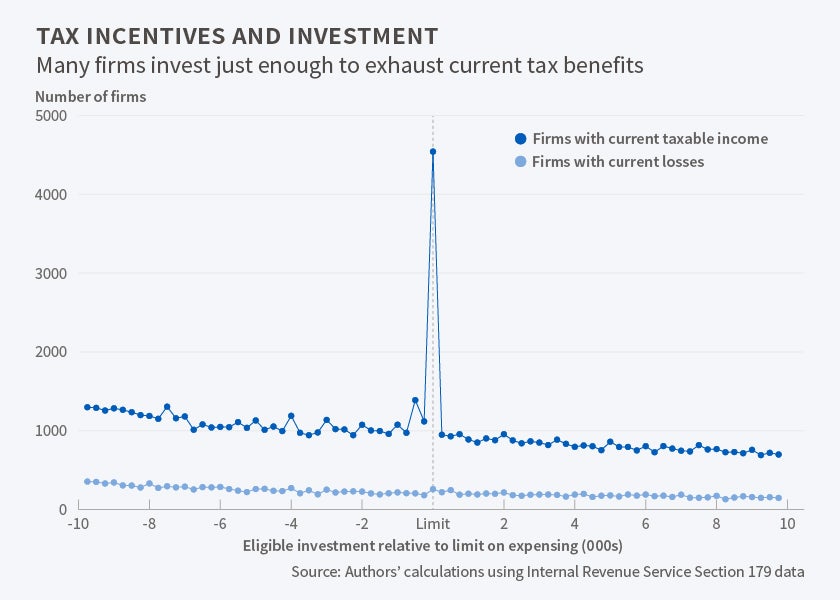

The study also finds that when there are limits on the amount of investment that is eligible for bonus depreciation, many firms undertake investments that fall within a few hundred dollars of this limit. When Congress raises the limit, firms raise their investment spending.

The authors investigate the characteristics of firms that take advantage of bonus depreciation, and find that they are disproportionately cash-constrained firms. Those that do not pay dividends, and that have low cash flow holdings, are between 1.5 and 2.6 times more likely to act on bonus depreciation incentives than their unconstrained counterparts. The findings support models of corporate behavior that emphasize liquidity considerations and financial constraints.

"The results imply that stimulus policies which target investment directly and yield immediate payoffs are most likely to influence investment activity," the researchers conclude. "Policies that target financial constraints might have a similar effect if conditional on the investment decision. In an approximate sense, bonus depreciation operates like a loan from the government."

—Laurent Belsie