Benefits and Costs of Healthier School Lunches

California data suggest that increasing the healthfulness of school lunches raises test scores for comparatively little cost, but that it does not appear to affect obesity rates.

Policies that provide subsidized school lunches are designed to improve student nutrition and support student achievement. The lunches available in different school districts vary along a number of dimensions, and, by standard metrics, some are healthier than others. In School Lunch Quality and Academic Performance (NBER Working Paper 23218), Michael L. Anderson, Justin Gallagher, and Elizabeth Ramirez Ritchie study the consequences of variation in the composition of student lunches. They find that offering healthier lunches delivers test-score improvements at a fraction of the cost of other interventions that strive for the same goal. They do not find, however, any association between the healthiness of lunches and student obesity rates.

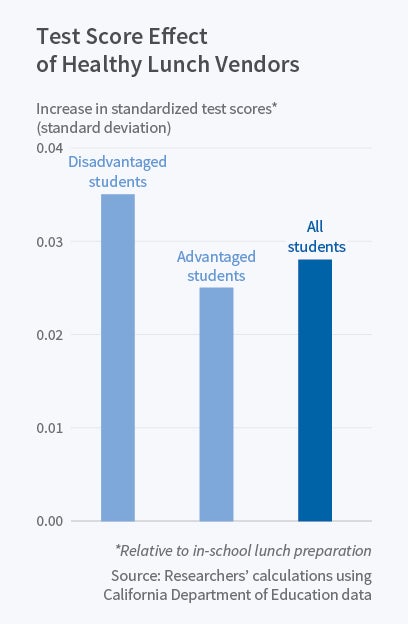

The researchers analyze standardized-test and food-service vendor data from all public elementary, middle, and high schools (about 9,700 schools) over a five-year period in California. About 12 percent of schools in their data sample contract with outside vendors for student lunches, and vendor contracts turn over frequently. They find that test scores are directly affected by both the introduction and the removal of healthy lunch providers, defined as vendors whose offerings scored above the median on an enhanced version of the Healthy Eating Index, a metric used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and public health researchers to assess diet quality relative to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. State achievement test scores increased by 0.028 standard deviations in a healthy-vendor contract year, relative to the year before the contract. Increases were greatest among economically disadvantaged students, who were eligible for reduced-price lunches.

The researchers found that the positive effect of healthy lunches persisted for the duration of a long-term contract. They also noted that districts that contracted with any outside lunch vendor — healthy or not — tended to have fewer economically disadvantaged students, and more Asian students, than districts that did not.

The number of lunches sold did not change upon introduction of healthier lunches, suggesting both that the test-score improvements were due to nutritional quality rather than a mere increase in calories consumed, and that the students did not find the healthier meals less palatable than the less-healthy alternatives.

The researchers conclude that providing nutritious meals is a relatively cost-effective means of achieving modest improvements in student performance on standardized tests, particularly for the most economically disadvan-taged students. They compare the relative cost of this approach with that of another well-known intervention: the oft-cited Tennessee STAR experiment, which was estimated to increase test scores by 0.22 standard deviations by reducing class size by one-third. The researchers note that "it would cost about $222 per year to raise a student's test score by 0.1 standard deviations through switching from in-house preparation to a healthy lunch provider. In contrast, it cost $1,368 per year to raise a student's test score by 0.1 standard deviations in the Tennessee STAR experiment."

The researchers also examined state-mandated Physical Fitness Test results to determine whether the healthy lunches reduced the percentage of students with body composition measurements outside of the "healthy zone" — that is, overweight and obese students. These percentages did not change significantly during the study period.

— Deborah Kreuze