Immigrants and Gender Roles: Assimilation vs. Culture

Source country gender roles influence immigrants' behavior in the United States, even among second-generation women.

Immigrants are an increasing presence in the United States. The share of the foreign-born in the population grew from 4.8 percent in 1970 to 12.9 percent in 2012, and the share of U.S. children who were immigrants themselves or who had at least one immigrant parent increased from 13 percent in 1990 to 23 percent in 2008.

Along with the rise in immigrant population has come a shift in the predominant origins of immigrants. The principal source of immigrants has shifted from countries in Europe, with cultures that are broadly similar to that of the United States, to regions with very different cultures and traditions. How much does an immigrant's source country affect their adjustment to American life? What role does assimilation play in that adjustment? Do differences between immigrants and natives in labor supply, education, and fertility carry over to the second generation, or do second generation women fully assimilate to native patterns?

In Immigrants and Gender Roles: Assimilation vs. Culture (NBER Working Paper 21756), Francine D. Blau reports on a research program with Lawrence M. Kahn that examines the roles of assimilation and source country culture as influences on immigrant women's behavior. The research focuses in particular on labor supply because immigrants increasingly come from countries that have a more gender-based division of labor than is currently the case in the United States. Typically, the source countries have lower female labor force participation rates and higher fertility rates than the United States. There has been a growing gap between the labor supply of native and immigrant women in the U.S. since 1980.

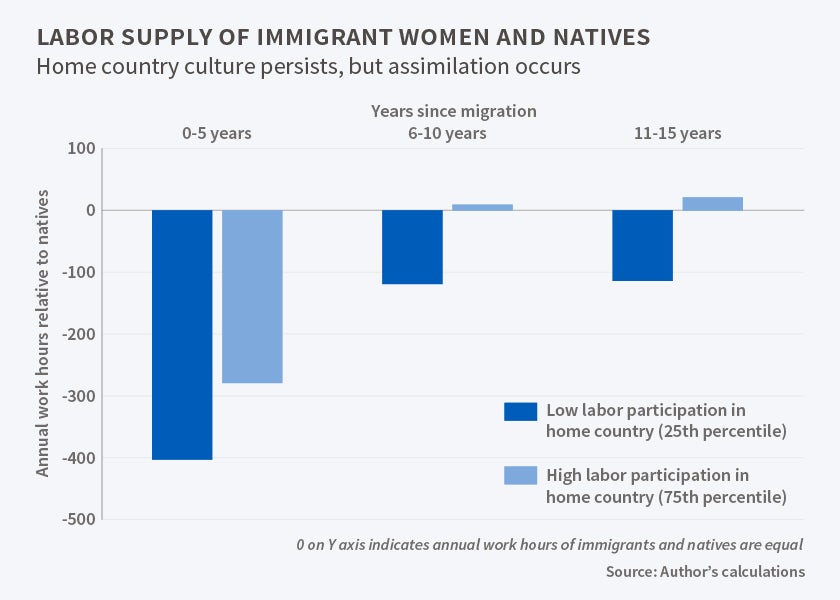

The researchers find considerable evidence that source country gender roles influence immigrants' behavior. This influence appears to extend to second-generation women. At the same time, they also find evidence of assimilation. Immigrant women narrow the labor supply gap with native-born women as they spend more time in the United States. There is also considerable convergence of immigrants to native levels of schooling, fertility, and labor supply across generations. For second-generation women, fertility and labor supply in their mother's source country have a larger association with their behavior than the corresponding practices in their father's source country.

Blau points out that in the future, immigrant source countries may become more similar to the United States, thus reducing the effect of source country gender roles on the behavior of first- and second-generation immigrant women. This has already begun to happen with respect to fertility. The fertility of immigrant women relative to natives has been falling rapidly in the most recent immigrant cohorts.

—Les Picker