Cash for Carbon: Payments for Conservation Reduce Deforestation

Paying landowners to conserve their forests slows deforestation at relatively low cost.

Trees absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis; they store the carbon in their biomass and release it when they die and decompose, or are burned as fuel. Worldwide, deforestation accounts for up to 15 percent of carbon emissions, second in carbon production only to the burning of fossil fuels.

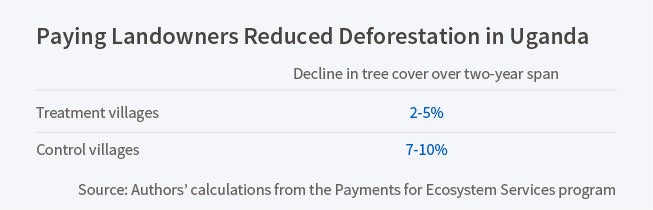

In Cash for Carbon: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Payments for Ecosystem Services to Reduce Deforestation (Working Paper 22378), Seema Jayachandran, Joost de Laat, Eric F. Lambin, and Charlotte Y. Stanton analyze a United Nations-funded Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) pilot program in Uganda. The program conducted a randomized trial in 121 villages from 2011 to 2013. Households in 60 villages were paid to refrain from cutting down trees, while those in 61 villages were not. The program put a significant dent in the pace of deforestation in the test area. Satellite imagery showed that tree cover declined by about five percent less in villages where incentives were offered, as compared with the control group.

The researchers found no evidence that participants shifted tree cutting to land not covered by PES agreements. They also determined that landowners who had previously planned to keep their forests intact were not disproportionately enrolled in the program. In fact, 85 percent of enrollees reported having felled trees in the three years prior to the program.

Only about a third of eligible households signed up for the program. The researchers suggest that participation would have been much higher had the program been better publicized, and had the communication dispelled fears that it was a ploy to confiscate land.

Since the program was short-term, the households could be expected to make up for postponed deforestation after it was over. But even delaying deforestation benefits the environment, the researchers note, though how much depends on the pace of renewed tree-cutting. Assuming a four-year catch-up period, they estimate that the program's benefits would be double its costs in payments to landowners and administrative expenses.

Because rural Ugandans are poor, the payments needed to compensate them for protecting the forest—and reducing CO2 emissions—are inexpensive in global terms. The researchers conclude that "per ton of averted CO2, this program is considerably less expensive than most alternative policies in place in the U.S. to reduce carbon emissions, such as hybrid and electric car subsidies." They also suggest that offering permanent incentives to discourage deforestation could offer more bang for the buck, although such programs need to be tried and evaluated.

The researchers tentatively estimate the cost of permanently preventing a ton of carbon dioxide emissions using forest preservation subsidies at $3.10. By comparison, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates the social cost per ton of carbon emissions at $39 in 2012 U.S. dollars.

—Steve Maas