Does Doctor Race Affect the Health of Black Men?

The life expectancy of black men is 4.5 years lower than that of non-Hispanic white men. Approximately 60 percent of this gap can be attributed to the higher rate of chronic disease among black men. As chronic diseases can often be prevented or effectively managed with lifestyle changes and medication, there are large potential health gains from ensuring that black men receive preventive health services. Yet black men are less likely to visit a doctor and to receive services like a flu shot, a gap that cannot be fully explained by education or insurance access.

A lack of diversity in the physician workforce may contribute to racial health disparities. Blacks comprise 13 percent of the U.S. population, but make up only 4 percent of physicians and less than 7 percent of recent medical school graduates. Black men have higher levels of mistrust of the medical establishment, likely due to the prominent history of abuse and neglect of disadvantaged populations by health authorities, such as in the syphilis experiment in Tuskegee, Alabama. Having a same race doctor may increase a patient's trust in their doctor's medical advice, but existing evidence is mixed as to whether patient-doctor racial concordance improves health outcomes.

In their recent study Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland (NBER Working Paper No. 24787), researchers Marcella Alsan, Owen Garrick, and Grant Graziani provide new evidence on the effect of doctor race on the health of black men.

To explore this issue, the researchers conduct a randomized controlled trial in Oakland, California. Over 1,300 black men were recruited to fill out a health questionnaire and given a coupon for a free health screening at a clinic set up for the experiment. Participants who came in for the screening were randomly assigned to a black or non-black (white or Asian) doctor. Participants were shown a photo of their doctor and asked to indicate whether they would like to receive any of a number of health screening services. Participants then had an opportunity to talk with their doctor in person and could revise their decisions regarding the health screenings.

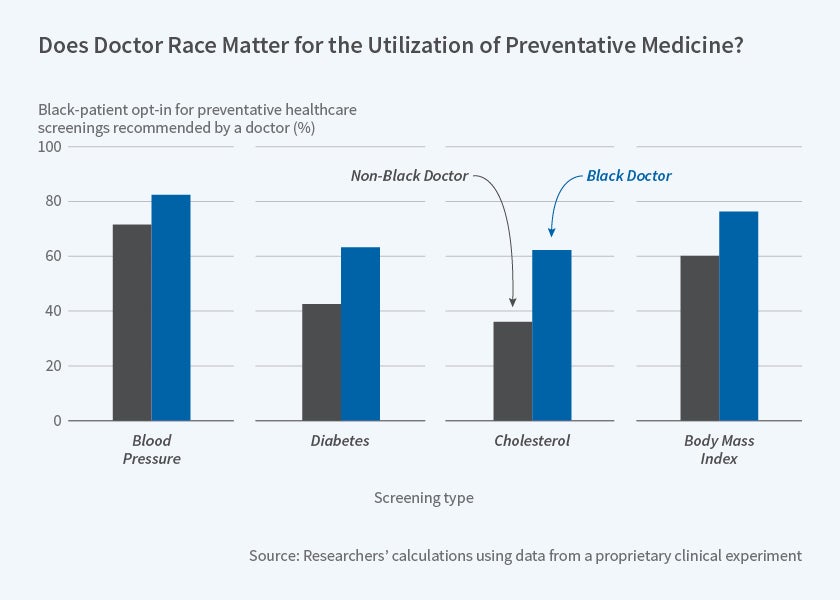

The researchers find no significant difference by doctor race in the initial take-up of screening services before patients have spoken to their doctors. However, after patients and doctors had a conversation, black male patients assigned to a black doctor had a much higher take-up of screening services than those assigned to a non-black doctor. For diabetes and cholesterol screenings, for example, being assigned a black doctor raised the probability of receiving the test by about 20 to 25 percentage points, which was an increase of 50 percent or more relative to the baseline rate of screening. Screenings for blood pressure and BMI were higher as well.

Better communication between same-race patients and doctors appears to be a key driver of these results. Patients were more likely to bring up other health problems when assigned to a black doctor and black doctors were more likely to write notes about their patients. Furthermore, while talking to their doctor increased take-up of non-invasive screenings — those not requiring a blood test or injection — for patients assigned to non-black doctors as well as black doctors (although the effect was bigger for those assigned a black doctor), take-up of invasive screenings only increased for the group assigned a black doctor. Invasive tests carry more risks and likely require more trust in the person providing the service.

The researchers simulate the potential health gains of the greater take-up of services that results from having a same-race doctor. Combining their findings with those from other studies about the health value of treatment, they estimate that having more black doctors could reduce the black-white gap in cardiovascular mortality by 19 percent and the overall black-white male gap in life expectancy by 8 percent. They conclude, "[g]iven the current supply of black doctors, a more diverse physician workforce might be necessary to realize these gains."

The authors acknowledge funding from the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab — Health Care Delivery Initiative, with supplemental support from NBER P30AG012810.